- Home

- Yvonne Young

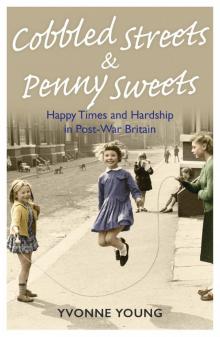

Cobbled Streets and Penny Sweets--Happy Times and Hardship in Post-War Britain Page 6

Cobbled Streets and Penny Sweets--Happy Times and Hardship in Post-War Britain Read online

Page 6

The slightest flicker of defeat crossed his face before he asserted himself once more, but I had seen that giveaway sign, which street kids are well aware of. We walked off and he scuttled back in his lair without a roar.

Our school was an old Victorian building with what seemed like lots of stone staircases leading all over the place. The ceilings were high and the toilets were across the yard outside, next to a disused air-raid shelter. I can recall going into the boiler room with a friend’s mother. Her husband was the boiler man and he was shovelling coal into it. I still remember being fascinated by the brilliant white light from the fire and the dry heat smell of coke burning.

The first half term meant time off school and I was off to my grandparents’ in Gateshead. When I returned home at the weekend, I just hung around the house, but come Monday, I went to the shops with Mam. She always met half a dozen women on the way there and back and stopped to chat while I rolled around the pavement in pure boredom, hopping, stamping, anything to break the monotony, when one neighbour asked:

‘Why is she off school, doesn’t look like there’s anything wrong with her?’

‘She’s not off sick, the school is on holiday.’

‘No, they went back today.’

‘Ah well, she can go in tomorrow.’

No panic at all, but of course she couldn’t admit to the teacher that she had simply forgotten, so it became necessary to write a note.

‘Ken, how do you spell diarrhoea?’

‘D… i… a…’

‘D… i…’

‘a… r…’

‘Hang on a minute, D… i…’

‘a… r, man!’

‘D… i… a… a…’

‘No, D… i… a… r…’

‘Oh, forget it! I’ll just put upset stomach.’

* * *

The form teacher called the register every morning:

‘Jane Smith?’

‘Present, Miss Trotter.’

‘Anne Robson?’

‘Present, Miss Trotter.’

After registration children brought their little tin to her desk with the correct change of dinner money. It was quite a cruel practice of teachers to mention the names of those who were taking free dinners. Children with a father out of work or from a single-parent family were immediately singled out. One lad from a large family was the owner of a knitted swimming costume, an old matted jumper which his mother had cut the sleeves off and sewed a crotch into. He did not escape the sleeves either as they were sealed at each end and he had to wear them as socks, big bulky things in his shoes. It must have been so uncomfortable, but families didn’t waste anything back then.

Mothers also bought jumpers from jumble sales to pull the wool out with the intention of creating new ones. Children in the family would be employed to unravel, wash and dry the wool, then stand with their arms out while it was wound around them. A man’s jumper from a sale would be prized as it would provide two children’s garments.

Children were often given jobs to do for the teachers. I was asked to take the cups of tea to the staff, so I negotiated my way with a cup and saucer with a biscuit on the side down around six sets of worn stone steps and into the yard, where Mr Scott was on yard duty. He said, ‘Oh, I don’t eat biscuits, you can have it.’

It was the loveliest taste, a custard cream. He swigged his tea quickly and gave me back the cup and saucer. On my return to collect another cuppa, the secretary said, ‘And this one is for Mr Scott.’

‘But I’ve just given him his tea.’

‘Mr Scott doesn’t like biscuits.’

She looked at the saucer, then at me.

I swiped my hand across my mouth.

‘This time, get it right! Take this to Mrs Clarke.’

I didn’t get the job again.

Mr Scott was new to the school – a very good-looking man, something that was also appreciated by Miss Belling. Being a woman who always wore her hair in a bun, she suddenly began to adopt a Diana Dors style, peering through one side of her hair while the other side was wrapped around her ear. Mr Scott took our class as form teacher and one of the first lessons showed our lack of knowledge. A map of the world was hung over the blackboard and he proceeded to point to various countries. We didn’t recognise any of them, even Britain was unknown to us.

‘What have these people been teaching you?’

Of course, being from our area, we were on the scrapheap before we even got going. What was the point, was their philosophy? We were all headed for factory work anyway in their minds. Mr Scott set to by changing the lines of desks into sets, pushing the desks together in groups, and children were organised by ability. Every Friday, he put the wireless on and you could hear a pin drop: this time it was a talk on Darwin and evolution.

Miss Belling was more interested in how things looked so we had to decorate the margins of our poetry books with flowers and birds and suchlike. We were given inkwells, italic pens and shown how to write in italics.

‘Hold your pens at forty-five degrees!’

During a swapping session with friends I was given two Penny Red stamps, so I took them into school to show the teacher. I forgot to take them with me at playtime and when I returned, someone had stuffed them in my inkwell.

When a supply teacher was assigned to our class we were asked to draw a house. It was common practice for us kids to draw the house square in the middle of the page with a little winding path with a garden, although none of us possessed one. The rooms could be seen and the light bulbs in each room aglow with light denoted by little lines forking outwards. No shades, what were they? A bed and kitchen with chairs drawn sideways on so they looked as if there were only two legs. I was first finished so I took my drawing to the teacher’s desk to be marked.

‘What’s this? Can you see into someone’s living room from the street? No! Go away and draw me walls, houses have walls.’

As I returned to my seat, everyone else was scribbling away furiously. This is what I call a ‘creative injury’ – I loved drawing and this experience didn’t deter me in later years, but what of those children who were affected by her lack of imagination? Thankfully, things have changed.

One teacher used to assign a couple of lads to wash his car on Friday afternoons. It was his pride and joy until after lessons one day when he returned to find the wheels gone, it was propped up on bricks and most of the accessories, such as wing mirrors and badges, had also disappeared.

Helen was a lass in my class who I sat next to for a while. She brought The Bobbsey Twins annuals into school and all of us girls wanted to read them. Her family went to Amsterdam for holidays and she was forever blatting on about tulips – there were tulip paintings in her home and various flower-related ornaments. I loved The Little Match Girl, The Tinder Box and The Little Tin Soldier stories. She was good fun and a right giggler. After being kept behind at the end of one school day for misbehaving, Helen and I were leaving by the main door when a man approached us.

‘Do you recognise this woman?’

‘No.’

We didn’t particularly take much notice of the faces as the group of adult males and females were naked, posing for a photo, all lined up as if they were at a wedding, brazen-faced.

‘This is Miss R,’ he said, ‘she goes to a nudist colony.’

What was that? But we didn’t wait to find out and ran to Helen’s flat, which was just behind the school. Her mother was peeling potatoes in a dish at the sink when we told her. Without putting the knife down, she pelted down the stone back stairs into the lane, shouting, ‘Where is he, where the bloody hell is he?’

She ran into the corner shop brandishing the knife at any men in there who were innocently buying cigarettes. We were close at her heels and managed to say that he wasn’t among them. The police were called to the school next day and me and Helen were interviewed separately. Nothing more was mentioned and we didn’t find out if they caught the man. It was probably a vindictive ex-boyfriend, th

at’s if it really was Miss R in the photo. Who could say?

Random men were not the only criminals connected with the school. One day, every class attended assembly to be faced with a wall of hymn books, prayer books and Bibles on the hall floor. There were dozens and dozens of them. Two girls were paraded in front of them and Miss Belling marched back and forth while the girls looked down, shamefaced, at the parquet flooring.

‘These two girls have been systematically stealing books from the school.’

Where on earth they were storing them in the small flats we all lived in is anyone’s guess, but even more puzzling was why they wanted them in the first place.

The assembly hall was also used for singing practice. Our class was chosen to represent the school in a contest to be held at the Newcastle City Hall. The chosen song was ‘Wintry Winds’. On the day of the competition we were taken to the venue by Miss Belling. When we removed our coats, she was aghast at my outfit: Mam had shoved me out the door that morning after putting this yellow sundress and matching bolero out for me to wear. It had a washed-out ink stain right on the front. Miss Belling took me by the top of my arm and roughly marched me out into the hallway.

‘We are representing our school and you turn up like this! You are a mess, a mess, do you hear? There are very prestigious schools here – Dame Allan, Jesmond – from all over the city. You will not stand in the front, I want you right at the back of the choir!’

She ensured that this was carried out personally. I was the shortest in my class and couldn’t see a thing, but I sang my heart out anyway.

* * *

The cloakrooms were a place of fun, huge wooden walls with arched metal bars which joined each one together. I was swinging back and forth when Ann decided that it would be a good idea to practise a flying trapeze move. She hung onto my ankles and set herself swinging, but I couldn’t hold on and went smack onto the concrete floor. My back was numb and I couldn’t move. Mr Scott was called and accompanied me to hospital until Mam arrived from work. I was off school for six weeks, severely bruised – I spent the time with the Romes at Gateshead as Mam couldn’t take time off.

I missed valuable lessons in arithmetic, although having said that, I wasn’t any good at it anyway. The only table I learned by rote was the ‘eights’, and that was as a punishment for something I had done in class. Even now, if anyone asks me what five times eight is I have to go through the rhyme to tell them. I also shudder at the mention of ‘If it takes six men two hours to dig a hole, how long will it take one man?’

I was well into writing poetry and always on the lookout for a subject. Around this time, the Bay of Pigs crisis was being played out in Cuba between America and the Soviet Union and I was really worried that trouble was going to find its way to our shores. I wrote a poem after a vivid dream which involved three tanks going up one of the streets in Benwell. An earth was on top of each tank: the first was green with water, the second engulfed in red and orange flames and the third was black. Two people were in the dream: one stood watching from the side of the road and the other was in front, sitting on a wooden bench. The Vickers factory was in the distance. The only line I recall was ‘The skies were grey and bled’. Later, my brother David painted a picture of this dream after I explained it to him.

During a poetry session held by Miss Belling, she called me out to the front of the class, threw my poem onto her desk and said accusingly, ‘You didn’t write this, you copied from somewhere!’

She wouldn’t listen to me when I insisted it was mine and sent me back to my seat.

A few weeks later, I was to have my revenge. Mam had been given a matted, shrunken jumper from a neighbour.

‘It will do for your Yvonne.’

It was a cream lumpy thing with a V-neck far too low for me so I pinned a glass brooch to close the gap. I wore it for assembly in the upper hall one morning and noticed that as Miss Belling charged back and forth at the front, she blinked as something irritated her eye. Quickly, I realised my brooch was casting a glint from the sunshine blasting through the window, so each time she was facing forward, I positioned that brooch with a flick of a finger and throughout assembly, and much to my delight the old bugger was tortured. I dread to think what would have happened had she discovered my wickedness.

The upper hall was also used for dancing and games on rainy days. Music was put on via an old record player and we pranced around happily until a bully of a lad in our class took great delight in pushing into the girls to knock them over. The teacher made him sit on the pipe running around the circumference of the hall. He began to fidget out of boredom and as he bounced up and down, his head dislodged the fire extinguisher, which crashed to the floor and set off a stream of water and foam. The bottle began to spin and shot off across the room, kids were screaming, yelling and dashing in all directions, while the teacher tried to regain control. A brave little lad who hadn’t been in our class long as he had been living in Australia – Jimmy was his name – threw himself onto the bottle and slowed it down.

The hall walls were decorated with an enormous frieze with a Greek mythology theme which our class had taken great pride in recreating over the period of a couple of months: full-sized Theseus and the Minotaur, The Labyrinth and Jason and the Golden Fleece. We had worked tirelessly to build up the stories in pictures. However, there was a fight in the classroom one day during crafts and a particularly naughty lad called Rob stuck a pair of scissors into the arm of a lad called Trevor and began to range around the room, holding the weapon above his head. Everyone screamed and Mr Scott pinned him down over a desk. Books and desks were strewn about as Rob kicked and struck out at the teacher. He eventually broke free and ran from the classroom into the hall. We all followed in total disbelief but that emotion turned to pure rage as we witnessed the little sod dragging his hand through the centre of our frieze all the way down the hall. Poor Trevor was nursing his arm while all this was going on.

* * *

When the Eleven Plus test was given out I did well in subjects such as English, Art and History, but for Arithmetic, I was informed that I had secured just one mark, which was only given for my name at the top of the page. Really, I had tried. Mr Scott was pulling out all the plugs to help us and for the first time gave out homework. When I read, ‘If it takes ten men five hours to dig a hole, how long will it take one man?’, I was in a right panic. I can remember feeling utter despair as I pleaded with my parents for advice on multiplication and long division to no avail. Next, from one to the other in the Rome household, which only resulted in a mass argument on who knew best, but none of them did. Back home on the Sunday night, Sarah had a dozen pals round to hers. I asked everyone and only one lad stepped forward. Give him his due, he battled for a good hour but I still couldn’t get long division hence I was destined for a telling-off – and for Atkinson Road Secondary Modern at the top of the hill.

At ‘Akky Road’, as it was known locally, the classes were made up of our lot from South Benwell, together with kids from other schools, all of whom hadn’t ‘passed’. I remember feeling really put out at having ‘failed’ as it was put to us. We secretly envied the schoolmates who had secured places at Rutherford, Pendower and John Marlay schools.

But I was soon to forget the ‘shame’ of being second best on meeting the other kids in my new class. Kenneth Fairbanks was cool, he had a quiff kept in place with Brylcreem. He got the nickname ‘Fairy’, but it didn’t bother him – he was too laid-back for that. I took a temporary dislike to him when he laughed at my bathing suit at our weekly lesson. Mam had bought me this horrible lilac thing, with rows and rows of flounce. I looked like a dirigible balloon and it earned me the nickname of ‘Frilly Bathers’ for a while until, thankfully, I was given a new one.

Older pupils were on the verge of leaving school to secure jobs. The lasses tatted their hair into Beehives, hair lacquer was sprayed liberally, but anyone who couldn’t afford it used a sugar-and-water solution. This attracted the bees, so mayb

e that’s where the name ‘Beehive’ comes from. The Beatles had just become popular and one of the older lasses had a white Sloppy Joe jumper on with ‘The BEETLES’ written on the back in pen and an ‘A’ written over the top of the second ‘E’. I had a little guitar badge with John Lennon inside a plastic picture circle.

I had begun standing in the corner of the yard with some of the older lasses. They smoked and seemed very risqué to me. One of them offered me ‘a drag’ of her cigarette and gave me instructions to suck in as hard as I could. Much to her delight, this burned my throat, but she probably did me a favour, as I was never tempted to try again. Besides, some of them picked up used fags and pulled out any remaining strands of tobacco to make a roll-your-own, which I found disgusting. My precious badge was nicked that day in the schoolyard and it wouldn’t have surprised me if it was that lass who took it. I have since seen the whole Fab Four set displayed in York Museum – I loved that badge.

The girls in my class took cookery lessons, which were split into weeks of either cooking, cleaning the ovens and pans or hygiene instruction. I once cooked a dish which involved an onion. I’d left it on the boil too long and it burned, leaving a black stain on the pan. I couldn’t be bothered to clean it so pushed it back onto the shelf. During afternoon break, Sarah also had a cookery session in her class and it was her turn on cleaning duty.

‘Some bugger put a manky pan back on the shelf and it took all afternoon to get the black off it!’ she moaned.

I didn’t own up.

For one hygiene lesson, we were asked to bring in a hairbrush. Each girl placed a piece of newspaper on her knee. A lass called Lynn Jones always came to school with the greasiest hair, her mop was known as ‘rat’s tails’. After brushing, everyone commented how lustrous her shiny hair was, we couldn’t get over it. But it was never like that again.

Cobbled Streets and Penny Sweets--Happy Times and Hardship in Post-War Britain

Cobbled Streets and Penny Sweets--Happy Times and Hardship in Post-War Britain