- Home

- Yvonne Young

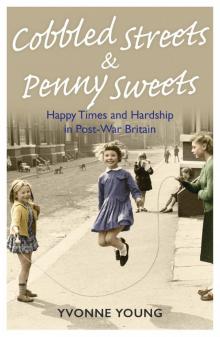

Cobbled Streets and Penny Sweets--Happy Times and Hardship in Post-War Britain Page 7

Cobbled Streets and Penny Sweets--Happy Times and Hardship in Post-War Britain Read online

Page 7

Mam was in her element that I was taking cookery at school. Once every three weeks, she didn’t have to think about placing a tin of beans or a packet of cheese on the table and could leave it to me to create Cornish pasties or corned beef pie. The teacher announced that we were all to make Fish Surprise and to bring in a tin of salmon for the next lesson.

‘What does she think she’s on,’ said Mam, ‘her granny’s yacht?’

‘Mam, I’ve got to have it, Teacher said! Everyone else will have a tin of salmon. Please, Mam?’

I went on and on until she relented. The dish consisted of mashed potato and salmon with breadcrumbs on the top. The teacher was annoyed because when she said ‘breadcrumbs’, we thought she meant to bring in a slice of bread, so she was forced to use all of her box of breadcrumbs on our fish pies. I took it home and put it on the table. Mam stuck her fork into it and tasted some.

‘Why, it’s nothing but a giant fish cake! What a waste of a tin of salmon!’

I didn’t mention that all the other girls had used pilchards or sardines – they mustn’t have whinged so much at their mothers.

I discovered Eggy Bread, a slice of bread dipped into raw whipped-up egg and fried, so at least this was something I could do myself. It was hardly a culinary masterpiece but a change from cheese and tomatoes. Besides, cheese was becoming a bore. Dad consumed copious amounts of the stuff and even if it had mould on it, he simply sliced the green parts off. Mam said that if it was off on the outside, it was certainly off on the inside, but this still didn’t deter him or encourage her to vary the range so unless I learned of a new recipe at school, flavourless fare was à la carte in our house.

* * *

I loved History lessons with Miss Jones. She taught us about the Seven Wonders of the World and I was entranced by the Ziggurat at Ur. Mr Bell sometimes taught us singing and was an excellent pianist, which inspired us to sing louder. He would crash his fingers on the keys, whizzing up and down the scales. But our regular teacher for Music was a very hefty lady who favoured singing the same songs at every lesson – ‘Camptown Races’, ‘The Water of Tyne’ and ‘Cushie Butterfield’ among her repertoire. She had to leave the room one day and in her absence, one of the lads put a drawing pin on her chair. When she came back in, we were all terrified she would get hurt, but didn’t dare say anything for fear of this lad. One brave soul, Graham, spoke up before she put her weight on the pin. She just assumed it had dropped there, so a huge sigh of relief went up.

Mr Kane was a Maths teacher. He caught a lad reading a comic during his lesson, clipped him around the ear with it and said, ‘Boy, if you are going to read a comic in my class, please have the sense to hide it behind a book!’

Of course, this gave carte blanche to the rest of us for future reference. Jerry wasn’t a confident lad and Mr Kane knew this so always asked him to read to the class. He started off quite slowly and then began rabbiting so fast to get it over with. None of us were laughing: Jerry was one of our own.

John Coleman’s family owned a shop which sold fresh fish, he was also a shy lad and a little slow. He came to school one day with his pyjamas clearly visible under his clothing, the hems covered his shoes below the trousers and the collar peeped over his shirt. Kane took it upon himself to bring John to the front of the class, ribbing him about his attire.

‘Is it chilly today, Coleman? Did you find it necessary to insulate yourself today? As a punishment, you will bring me some fishcakes tomorrow.’

He looked around the room, waiting for a laugh and approval of his behaviour, but he received none.

I was surprised that I didn’t become the butt of his jokes as I was so poor at Arithmetic and he was supposed to be teaching that very subject. With hindsight, I don’t suppose he even looked at our work to mark it. Yes, this reinforced the notion that we were classed as fodder for the factory.

English classes were well-liked, with Mr Cooper at the helm. He looked and sounded like the comedian Frankie Howerd. He was nicknamed ‘Mad Jack’ because he didn’t take any nonsense from the older kids at the school, who were noted for causing some teachers to burst into tears, pelting chalk, blackboard rubbers at each other, running around in class and clashing the lids of their desks. One day, MJ announced that he was going to write his new song on the board. He proceeded to chalk the lyrics to ‘Swinging On A Star’, to which everyone began shouting out and laughing.

‘Sir, somebody already wrote that!’

‘Diiiid theyyyyyy nowww?’

We became really excited and jolly, then he snapped and began throwing chalk at us. We were ordered to read to ourselves. Jock of the Bushveld was the group book and a lass called Kathleen was so engrossed, she shouted out, ‘Mam, put the kettle on!’

Everyone fell about laughing. Kathleen was ordered to stand in the corner for the rest of the lesson.

Still, he wasn’t as bad as one teacher at the neighbouring Denton School, who used a water pistol to fire at pupils!

* * *

Science lessons were offered by Mrs Clements. She demonstrated the dangers of smoking by puffing through a white handkerchief, which turned the fabric yellowy blue.

‘This is what’s deposited on your lungs, it’s tar.’

She organised a trip to the local General Hospital, where we were treated to observing a set of lungs floating in jars of formaldehyde for research purposes. The doctor pointed out the white patches on the organs. He explained that when a person has a smoker’s cough, it is due to the lungs hardening and turning the texture like that of a leather shoe. They find it difficult to breathe, he said, and this causes cancer. I often wonder if any of the smokers in our class who sneaked out to the toilets across the yard continued to do so after that day.

The main hall was used for morning assembly, as a dining area and for gym lessons and country dancing. There were wooden climbing bars from floor to ceiling on the walls. I was sent on an errand one day. As I walked around the balcony there was a sports lesson going on, with older lads jumping over the horse and climbing up ropes. One lad hated these lessons so persuaded his mates to hide him inside the box, where he sat until it was finished, listening to the thudding as lads vaulted over him. The school took delivery of new Velcro-edged rubber mats with sponge inside. This lad decided that he would take part for a change and wrapped a mat around himself. With only head and feet on show, he shuffled round the polished oak floor, shouting, ‘I am a Dalek!’ The headmaster glared from his office and then raged over the balcony, ‘You, boy! You stupid boy, get up here NOW!’

The lad got such a shock that he went over like a felled tree, trapped on the floor like a giant sausage roll, until someone tore the Velcro apart. Such a daftie but at least he was allowed Woodwork lessons, which the girls were barred from. I wanted to make a coffee table or an ashtray like the boys did (not that we’d have used an ashtray for its intended purpose in our house as my parents didn’t smoke), so why was this not allowed? For all I enjoyed sewing and cookery lessons I could never understand this. Surely there were some lads who didn’t enjoy practical skills and they could have allowed the odd lass into the Woodwork room, but we were never given the option (it wasn’t until the nineties that I began a course where I learned carving, how to use a lathe and a bandsaw). Mam bought me a sewing machine – a Jones electric with a pedal, it was iron and weighed a ton. All of the ones I had seen before this were old treadle models. I chose it at the Co-op on Newgate Street and couldn’t wait for it to be delivered so I begged her to allow me to bring it home there and then. I dragged it along the path, this iron giant, stopping every few minutes, but she refused to help. Of course, one of the first things she did once I mastered its use was to go to Farnon’s department store to buy fabric and curtain tape!

Mam wasn’t big on ironing (or washing, come to that). I made a gorgeous cream corduroy skirt and first time in the wash, she hung it dripping wet on a rusty rail in the cupboard – the red stain went right through it. I took care of my own laund

ry after that. But with both my parents, I had a problem with anything new which I purchased. Dad worked in a garage and had a stupid habit of washing his oily hands in the sink. Before rinsing them, he would pick any item from the basket and ‘Get the thick off’. More things were ruined in this way.

CHAPTER THREE

Catechism, Camping and the China Cabinet

St Aidan’s was an old Protestant Gothic church and hall which stood on the corner of St John’s Road and Joseph Street in Elswick. As children, we knew that if we stood outside long enough on Saturdays, there was bound to be a wedding. As the happy couple drove away, it was customary to throw coins out onto the street (known locally as ‘The Hoy Oot’). There would be a mad scramble and we picked up as much as we could get our hands on.

Waiting for the couple to become man and wife, I noticed a lad who had caught a starling. He told me that he was training it – he was a falconer and it would come back to him like the eagles do. He had tied the poor creature’s legs with string and began whirling it around so the legs were pulled from their sockets – I couldn’t bear to see this. However, we all knew that if anyone had tried to stop him, we’d have been beaten up.

This wasn’t the first time I had witnessed such barbarity. Me and Sarah used to go over St John’s graveyard after church to look for a lonely-looking plot on which we could put a few daisies or clover to ‘decorate it’. One day, an older lad was intentionally pulling the legs from a homing pigeon to take the little metal identification rings.

Some of the kids in the area were little criminals in the making. I once saw a group of wasters stealing bottles of Domestos from a shop. They emptied the contents onto the grass, then went back in to claim the pennies back from returns. But none of this was so disturbing as what some did to defenceless wild creatures.

* * *

Christmas bazaars and jumble sales were held at St Aidan’s, but never garden fêtes, as the back of the church grounds were covered in weeds. One year, Mam saved up in the church club to buy a dinner service – although she didn’t attend services, she liked the fairs. The cups were painted inside and out (and the plates and saucers too) with a hunting scene, dogs and horses with riders in red coats. ‘It’s real bone china!’ she kept saying. She aspired to own a china cabinet one day, so this set would definitely not be in use.

There was always a good supply of volunteers to man stalls. I enjoyed listening to the women chattering and discussing what the other members of the congregation were wearing, including the Vicar’s wife. Half the time I didn’t understand what they meant, some of it went over my head, but I craned my neck to hear.

‘She’s always beautifully dressed, that shows respect.’

‘Yes, I love that frock she wore today and she always bows so low before Communion that her knee touches the floor.’

‘Very respectful, very respectful.’

‘But he’s trying to make it too High Church.’

I do remember that the Reverend gathered a few of us together to introduce Confession.

‘What’s that?’ we asked.

‘We all need to be sorry for our sins,’ he said.

But this wasn’t to be done in boxed-off cubbies, as in Catholic churches, but in the pews next to each other. We sat there trying to think of something we had done wrong, so he helped us along a little.

‘Maybe you have been unkind to a friend?’

Yes, that would do, so we all offered that up as our Confession. The idea didn’t catch on.

His next project was for us to be shepherded into Confirmation. Around six of us showed an interest, me and my pal Sarah, who knew about such things.

‘It means you get bread and wine on Sundays.’

This sounded OK to me so we signed up. So we met at the Church House, family home of the Reverend and his wife and two children. We were led through the vestibule into a library – a library in someone’s home? The most luxurious space I had ever experienced, there were beautifully bound leather volumes, a writing desk and paintings on the walls. It sure beat the socks off Dad’s Charles Atlas body building manual. When I asked Mam why he used it, she said, ‘Because he doesn’t want anyone to kick sand in his face.’

She read me a story when a book was sent home from school by a teacher. It was about a little pink pig and I have always held that memory. I felt so secure, cuddled up to her. It never happened again. Around then I was also becoming increasingly aware of arguments between my parents which ceased when I walked into the room.

Anyway, floor-to-ceiling bookcases lined the four walls of the vicarage, there was a huge desk, patterned carpets and a coal fire surrounded by beautiful patterned tiles and a golden fender with a little stand nearby, sporting a brush and shovel. This seemed like a mansion to me, coming from a damp, near-crumbling property as I did. There was a bay window in our front bedroom which leaked water when it rained, so buckets were plentiful in our gaff. Our homes were labelled unfit for human habitation before World War II. They had been solid structures, but weren’t kept in good enough repair.

In the end there were only two of us going to read and learn the Catechism and then Sarah dropped out after a few more sessions because she couldn’t memorise any of the text. But I loved sitting in that room so it was worth it. When the Reverend asked me who I would like my sponsor to be, he could tell from my blank expression that I hadn’t a clue what that meant, so he volunteered, saying:

‘I do know a very nice parishioner who would be willing to take on the role. She will guide you in the church, a little like a godparent.’

Mrs Anderson presented me with a prayer book covered in plum leather, which I still have to this day. Also, a tiny little box. I opened it and inside was the most beautiful real silver cross and chain. Wow! It was delicately patterned in a kind of Celtic design. That was the last contact I had with her.

I did join the Brownies. One of the older members of the group gave me a brown dress of dull brushed cotton and I was given a spare hat and yellow tie from the Brown Owl. Tawny Owl was in charge of putting us into our groups: there were Elves, Gnomes and I was placed with the Pixies.

This is what we do the Elves, think of others not ourselves.

Here you see the laughing Gnomes, helping Mother in our homes.

Look out, we’re the jolly Pixies, helping people when in fixes.

Fair enough, not too many words to learn, but it came to the time when parents were invited to watch us perform a little play on the stage in the hall. Brown Owl decided as there weren’t enough groups, she created another one called Sprites and took one girl from each of the existing groups. This happened on the night of the show.

Here we come, the sprightly Sprites, brave and helpful like the knights.

But it wound up a complete mix of the songs we had already learned in our respective groups and descended into a jumble of incoherence. My parents didn’t attend, which was probably just as well.

We were told there were many badges of achievement and our first task was to use a public phone box to make a call. Tawny Owl would be near the phone in the vestry and we were to find the nearest street where one could be found. She gave us some pennies and off we went. It seemed to take ages to find a phone box that hadn’t been vandalised. Being short arses, it took all three of us to pull the heavy iron door open and we could hardly see what we were doing in there. We made so many mistakes that we lost the money. Probably because we didn’t understand that button B had to be pressed to retrieve it! I’m sure both Tawny and Brown Owl thought we had purloined the cash.

Every now and then there would be a games evening at the church: Hangman and Beetle Drives. On Sundays, after service and the coffee morning, the men played billiards or snooker. I never knew which, only that they used a green table, knocked balls around with cues and wrote numbers on a board with chalk. It was really addictive to watch.

As I was about to celebrate my Confirmation Day in church, the Reverend dropped into our house on his rounds in the

neighbourhood. There was a tin of sardines on the table. Mam pretended they had been left out by mistake.

‘Oh, what’s that doing there?’ she said, picking it up swiftly and putting it back in the kitchen cabinet.

‘We don’t eat those very often,’ she added.

Oh yes, we bloody do! I thought, but didn’t say anything.

I have no memory of Mam’s attendance at my Confirmation, but I do know that Dad was definitely not there as he was always out doing his own thing.

I was asked by another girl in my class to attend a social evening at her place of worship, which was on Buddle Road, a Methodist church. Tea was served in cups with saucers. Mine was too hot so I poured a little into the saucer and blew on it to cool it down. I was never asked again, but kept badgering her.

‘My mam says you can’t come back,’ was the eventual explanation.

Maybe I was slurping. For a while I felt common, but it was really Mam’s fault for not using the bone china.

* * *

I joined St Aidan’s Guiding community when I was a little older. Once more, I was given a hand-me-down: this time a navy wool skirt from a friend’s elder sister, who had grown out of it. I went to the house to pick it up. The family had a little Westie dog, which was old and blind and kept bumping into furniture – he only moved out of the basket to go for a pee. The skirt was so lovely, I even wore it for everyday use. We did similar activities to the Brownies, but the badges were gained from more complicated tasks: cookery, for one. I couldn’t very well ask advice from my mam as she didn’t cook.

She set out a dinner once a week on Sundays: lumpy gravy, lumpy potatoes and tinned meat. On occasion she would attempt a roast. We had a set of six Pyrex dishes with lids (there was only one left without a lid by the time we moved house). Once the meat had been placed on a plate, she had a habit of dunking the dish in cold water straight from the oven so it cracked clean in half. Otherwise she would plonk a bag of tomatoes and a half pound of cheese on the table, or a tin of beans or sardines. After lunch, she dismantled the pipes of the oven, cleaned and put them back together and it wasn’t in use again until the following Sunday. But she did make a very lovely rice pudding on Sundays: egg, milk, rice and lots of sugar, always with a skin on top. It sat in a metal dish on a low heat for a couple of hours.

Cobbled Streets and Penny Sweets--Happy Times and Hardship in Post-War Britain

Cobbled Streets and Penny Sweets--Happy Times and Hardship in Post-War Britain